Mobilising Children’s Agency for Eliminating Corporal Punishment

Being a victim of circumstances and other people’s actions is a painful experience. When children are the ones who undergo violence by their teachers and parents, the pain could be incapacitating. However, my experience of working with children for over a decade has taught me that they possess astounding strength which typically remains latent. Is it possible to harness this potential to combat the phenomenon of corporal punishment? Is it even ethical?

I firmly believe that the responsibility of eradicating violence against children rests solely on us, adults. I do not suggest that children share this burden in any way. It is the responsibility of teachers, the parents, the government, and other influencers to take ownership and act. However, if empowering children can help influence the behaviour of other social actors, then there is no reason not to utilize their power. But how do we do it?

We have tried mobilising children in our work on eliminating corporal punishment in India along with other behavioural, systemic, and cultural shifts we have been attempting. Sharing three key insights that can be applied more broadly.

First, children find it easier and faster to unlearn, break old mental models and formulate new ones. “But if we don’t punish the children will get spoilt” is one sentence my team hears every day. Most teachers, the parents, government representatives and even the “educationists” find it almost blasphemous to question this thinking. Children, at the beginning of our work with them, often share how a good teacher is someone who would punish them for their own good. However, a well-designed intervention with them lead to fundamental and sustained shifts. These newly created mental models are critical to question the wickedness of corporal punishment before we act to fight it.

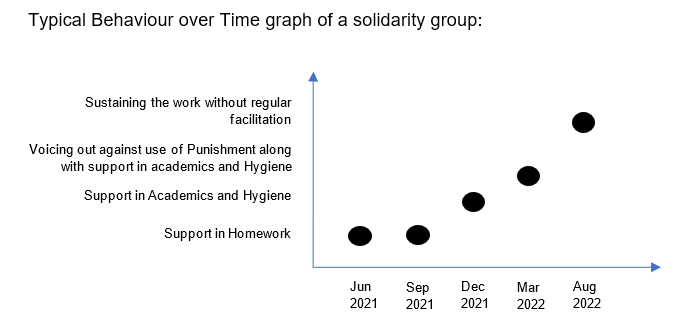

Second, children have a natural bias towards action. In a world where adults often speak more than they act, children tend to set goals and take direct actions towards achieving them. This holds particularly true when they are members of a facilitated team. The progress plotted over a Behaviour-Time Graph of solidarity Groups formed by Agrasar in India substantiate the leadership taken up by children as soon as they start witnessing the change.

In this blog Prerit Rana, Chief Executive of Agrasar, describes how they have included efforts to mobilise children in their efforts to eliminate corporal punishment in India, along with work towards other behavioural, systemic, and cultural shifts. He shares three key insights that can be applied more broadly.

Contact: prerit@agrasar.org

Third, children don’t keep old grudges. They thrive on compassion. Weren’t we like that in the past? Actions grounded in the universal values of compassion and oneness are essential to fight the evil of corporal punishment. And children are the ones who show us the way. They inspire the teachers and the parents to be like them. Teachers often have “favourite” students and also those who they loathe. Even best of teachers we have worked with have expressed this tendency. Some more evidently than others. This often result in changing the forms of punishment towards these “difficult students” even after regular participation in the Agrasar’s “good teacher” workshops. However, we have hardly come across a child in India who hated her teacher. They surely despise the punishment, but always keep deep affection for the teacher intact. So, even when they learn the harmful affects of punishment and how to raise voice against such acts they never go up to a point wherein they make the teachers feel disrespected. Rather, numerous teachers have reported how warmly their students have responded to the modified method of teaching and discipline and how that has encouraged them to do even better. Their stories are amazing!

A line of caution at the cost of sounding repetitive. The onus of fighting the pandemic of corporal punishment is on us, adults. While the power of children should be utilized, they should not be burdened with solving problems we have created for them.