Corporal punishment and health

Over 50 years of research illustrates how corporal punishment violates not just children’s right to freedom from all violence, but also their rights to health, development, and education, and has damaging effects on society as well as individuals.

Considering the strong evidence of the many negative impacts of corporal punishment combined with its very high prevalence, corporal punishment of children could be considered a public health crisis.

Prohibiting and eliminating corporal punishment is a critical preventative health strategy

Prohibition and elimination of corporal punishment can be understood as a low-cost public health measure, critical in preventing injury and disability in childhood, emotional trauma and mental illness, anti-social behaviour and aggression, and promoting optimal welfare, development and educational outcomes for children, which last throughout life.

Evidence also suggests that eliminating violent punishment of children may reduce other forms of violence in society, including domestic, intimate partner and gender-based violence, and diminish drug and alcohol abuse and suicide in adulthood. Find out more about the research on corporal punishment.

The implications of corporal punishment for public health

- Very high prevalence

Enormous numbers of children experience corporal punishment in their homes, schools, care and work settings and the penal system in countries across world regions. The Know Violence in Childhood 2017 study estimated that 1.3 billion boys and girls aged 1-14 years experience corporal punishment at home.[1] UNICEF MICS studies frequently find high levels of physical and psychological punishment of children.[2]

- Direct physical harm and abuse

Corporal punishment kills thousands of children each year, injures many more and is the direct cause of many children’s physical impairments.[3]

Most violence against children commonly referred to as “abuse” is corporal punishment.[4] All corporal punishment, however mild or light, carries an inbuilt risk of escalation. Studies suggest that parents who used corporal punishment are at heightened risk of perpetrating severe maltreatment.[5]

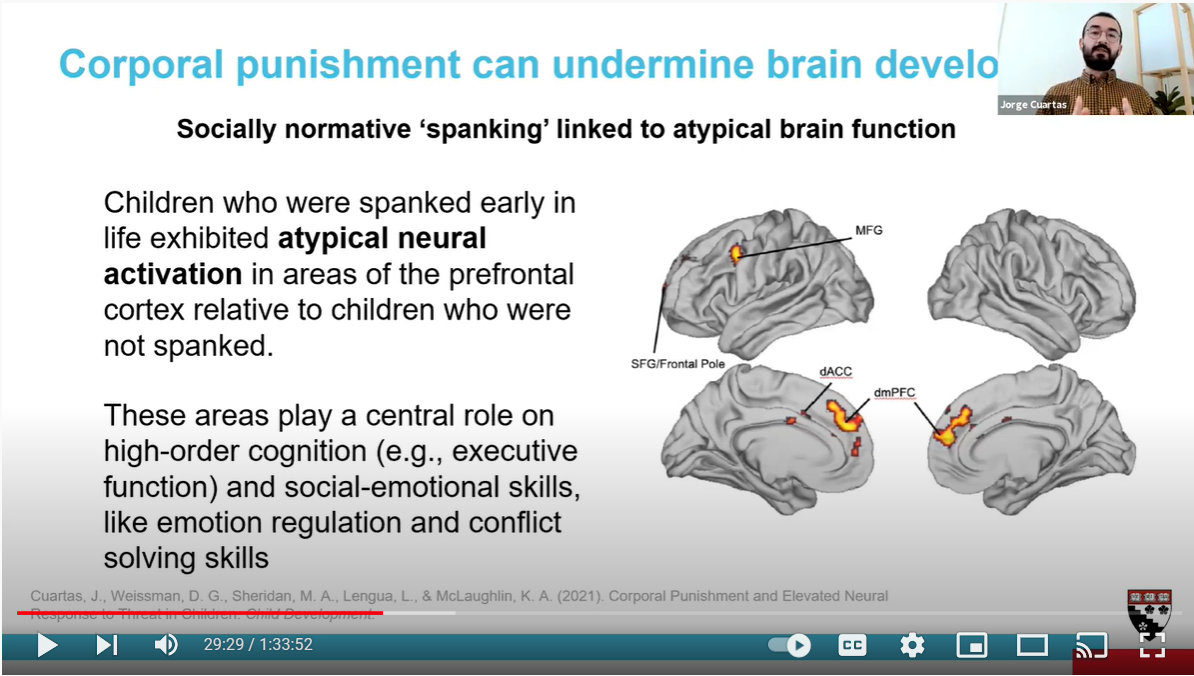

Even more “moderate” corporal punishment is associated with atypical brain functioning.[6]

Ending corporal punishment is essential in ending physical “child abuse”. The legality of corporal punishment undermines child protection: it reinforces the idea that a certain degree of violence against children is acceptable.

- Strong links between corporal punishment and negative impacts on mental health

Two major meta-analysis in 2002[7] and 2016[8] reviewing evidence from studies involving hundreds of thousands of children found associations between corporal punishment and:

- behaviour disorders

- anxiety disorders

- depression

- hopelessness

- low self-esteem

Later studies have confirmed these associations and found further links with suicide attempts, alcohol and drug dependency, hostility and emotional instability, self-harm and other mental health problems, with increased risk continuing into adulthood.[9]

- Indirect physical harm

Associations have been found between corporal punishment and health issues in childhood and youth, including asthma, suffering injuries and accidents, being hospitalised, and developing habits which put their health at risk, such as smoking, fighting with others and alcohol consumption.[10]

Corporal punishment in childhood is also associated with adulthood health issues including developing cancer, asthma, alcohol-related problems, migraine, cardiovascular disease, arthritis and obesity as an adult.[11]

Connections between corporal punishment of children and wider violence in society

The negative effects of corporal punishment on individual children and adults add up to negative effects on society as a whole.

Research suggests that the more a society approves of violence for certain purposes (eg. corporal punishment of children), the more individuals in that society are likely to use violence more widely; and that the approval and prevalence of corporal punishment in societies is linked to the use or endorsement of other forms of violence, including fighting, torture, the death penalty, war and murder.[12]

A few states have carried out research on the impact of their prohibition and efforts to eliminate corporal punishment. The wider positive effects of the decreased acceptance and use of violent punishment of children are becoming visible[13]:

- Sweden – associated decrease in the number of 15- to 17-year-olds involved in theft, narcotics crimes, assaults against young children and rape and a decrease in suicide and use of alcohol and drugs by young people

- Finland - associated decline in the number child murders

- Germany – associated decrease in violence by young people in school and elsewhere and in the proportion of women experiencing physical injury due to domestic violence

Eliminating corporal punishment is a global development priority

The elimination of violence against children including corporal punishment is called for in several targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Most explicitly in Target 16.2: ‘End abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence against and torture of children’, but also SDG 3: ‘Ensure healthy lives and promoting well-being at all ages’, SDG 5.2.1 ‘Eliminate violence against women and girls’, SDG 4: ‘Quality education’, and others.

Health-related resources

References

[1] Know Violence in Childhood. 2017, Ending Violence in Childhood, Global Report 2017.

[3] Krug E. G. et al (2002), World Report on Violence and Health, Geneva: World Health

[4] https://endcorporalpunishment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Research-effects-summary-2021.pdf

[5] Straus, M. & Douglas, E (2008), “Research on spanking by parents: Implications for public policy” The Family Psychologist: Bulletin of the Division of Family Psychology 24(43), 18-20

[6] Cuartas, J. et al (2021), “Corporal Punishment and Elevated Neural Response to Threat in Children”, Child Development, Volume 92, Issue 3

[7] Gershoff, E. T. (2002), “Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review”, Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539-579; see also E. T. Gershoff (2008), Report on physical punishment in the United States: what research tells us about its effects on children, Colombus, Ohio: Center for Effective Discipline

[8] Gershoff, E. T. & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016), “Spanking and Child Outcomes: Old Controversies and New Meta-Analyses”, Journal of Family Psychology, advance online publication 7 April 2016

[9] https://endcorporalpunishment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Research-effects-summary-2021.pdf

[10] https://endcorporalpunishment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Research-effects-full-working-paper-2021.pdf

[11] Research-effects-full-working-paper-2021.pdf (endcorporalpunishment.org)

[12] Straus, M. A. et al (2014), The Primordial Violence: Spanking Children, Psychological Development, Violence, and Crime, NY: Routledge

[13] https://endcorporalpunishment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Summary-of-research-impact-of-prohibition.pdf