Guest feature: Estimating the global prevalence of violent and non-violent discipline in early childhood

Why this matters

Research into the prevalence of corporal punishment of children and societies' attitudes towards it helps to support rights-based measures aimed at ending violent punishment in childrearing and education. It makes the issue visible, challenging claims by some governments that it is not a problem, and it provides a benchmark for measuring the success of efforts to implement prohibiting legislation and eliminate corporal punishment in practice. When research directly involves children, it helps to give them a voice, exposing what happens to them in schools and in the privacy of their own homes.

Discipline is a system of teaching and nurturing aimed at providing guidance, boundaries, and finding solutions to conflict. As such, discipline is a fundamental component of child-rearing, which is more effective when coupled with supportive relationships and clear strategies for teaching positive behaviors while reducing negative behaviors. Both scientific research and principles of child rights suggest that positive discipline methods are non-violent in nature and are most effective in fostering self-regulation while guaranteeing children’s rights and wellbeing. Yet, other socially accepted forms of “discipline” can be considered as negative, including corporal punishment. In particular, corporal punishment is a major stressor that children experience since their first days of life, which according to more than 50 years of research has the potential to compromise children’s healthy development.

Despite the importance of discipline early in life, little was known about the prevalence of different disciplinary practices, including corporal punishment, in low- and- middle income countries (LMICs). Is corporal punishment common throughout LMICs, and does corporal punishment coexist with alternative, non-violent practices? According to prior studies corporal punishment was a common practice in LMICs, however little was known about the prevalence of alternative, non-violent disciplinary strategies. Moreover, the existing research focused in countries with available data from UNICEF’s Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey (MICS) or the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), making it difficult to understand the prevalence of different disciplinary practices in countries traditionally excluded from these surveys.

Study

Within this context, we conducted a study with Dana McCoy, Catalina Rey-Guerra, Pia Britto, Elizabeth Beatriz, and Carmel Salhi to estimate the global, regional, and national prevalence of different practices used to discipline 2- to- 4-year-olds in 2013. To do so, we employed data for 49 countries from the MICS about different disciplinary practices, as well as country-level data about socioeconomic and demographic conditions of 131 LMICs. Using these data, we fit statistical models, developed through cross-validation techniques, to estimate the prevalence of disciplinary practices in the 82 LMICs without data in the MICS. Indeed, using cross-validation techniques allowed us to select the most accurate predictive model (minimizing prediction error) based on a group of country-level variables such as the Human Development Index, the Gini Index, and the presence of bans on corporal punishment, among other characteristics.

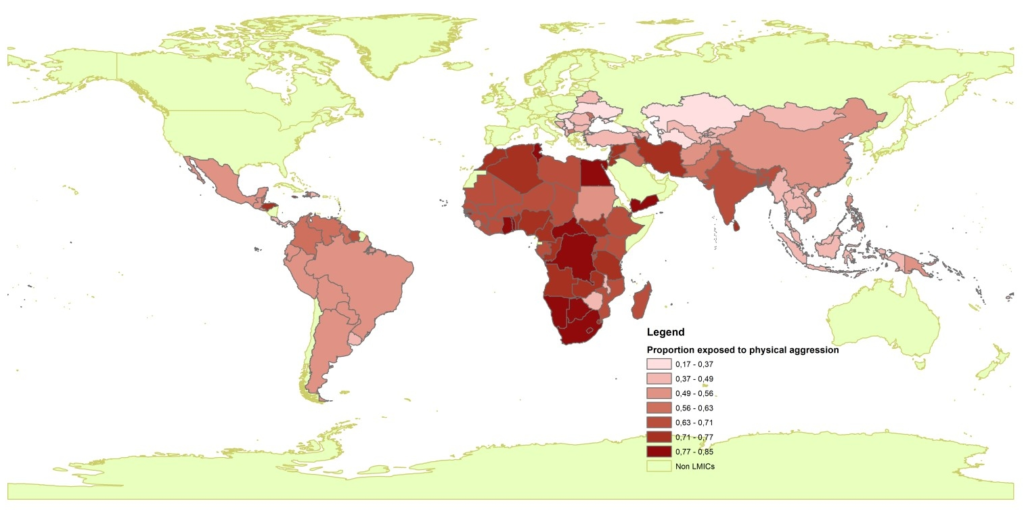

Using the best-fitting predictive model, we estimated that 296.2 million 2- to- 4-y-olds living in LMICs were disciplined using non-violent methods such as explaining why the behavior is wrong or time-outs, which corresponds to almost 84% of the population in that age range. Nonetheless, 220.4 million kids (around 63%) were corporally punished, with a higher prevalence in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 1). Moreover, our estimates revealed that around 48% of children were exposed both to physical punishment and other forms of psychological aggression, and that 66% were exposed both to violent and non-violent disciplinary practices. In the published article we provide the prevalence of each disciplinary method by country.

Findings

Our findings revealed that corporal punishment is still prevalent in LMICs, and often coexist along with alternative, non-violent disciplinary methods. As such, fostering positive discipline would on its own be unlikely to eliminate corporal punishment, so targeted interventions are needed to reduce the prevalence of violent discipline worldwide. Recent reviews of the literature suggest that there are several interventions that may have the potential to reduce the use of corporal punishment, yet most of the existing studies have been conducted with samples from high income countries so more research is needed in LMICs. Some promising interventions could be providing information to parents through baby-books, via pediatricians, and through massive media. Such information should not only focus on the potential risks associated with corporal punishment, but also on feasible alternatives that parents could use to effectively foster their children’s self-regulation.

Importantly, action is needed at the policy level. To date, 54 countries have achieved prohibition of corporal punishment in all settings, including at home. Legally prohibiting the use of corporal punishment should not constitute an additional source of stress for families, but should leverage additional supports for parents and other caregivers to engage in positive practices and must be aimed at sending the message that no form of violence against children is acceptable. Furthermore, achieving the legal prohibition of corporal punishment is aligned with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Sustainable Development Goals, target 16.2 and the advice of UNICEF’s and other professional organizations. More importantly, doing so will be consistent with the objective of reducing children’s exposure to risk factors to help all children achieve their developmental potential.

Figure 1. Estimated proportion of 2- to- 4-y-olds exposed to corporal punishment in LMICs, by country.

Guest writer

Jorge Cuartas, Ph.D. Student, Harvard University

Jorge Cuartas is a Ph.D. student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and graduate student affiliate at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science. His research focuses on the analysis of human development and parenting in contexts of adversity, the effects of physical punishment on children's developmental trajectories, and policy and program evaluation in low- and- middle income countries. Jorge is also co-founder and co-director of Apapacho, a non-profit organization aimed at fostering positive parental practices and contributing to peace building in Colombia. He holds a M.Sc. in Economics from Universidad de los Andes and a B.Sc in Economic from Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano.

Contact: jcuartas@g.harvard.edu

Twitter: @jcuartas2

Related resources

Cuartas J. et al (2019) "Early childhood exposure to non-violent discipline and physical and psychological aggression in low- and middle-income countries: National, regional, and global prevalence estimates" 92 Child Abuse & Neglect 93-105