Guest feature: Push and Pull Strategy to End Corporal Punishment in Indonesia

Why this matters

Although sometimes initiated and enacted quickly by Government, more often prohibition of corporal punishment is achieved after a long campaign by local advocates. Taking a strategic approach to law reform allows planning for the stages of a campaign over time, incorporating information gathering, public education and awareness raising, political advocacy, and consideration of the implementation of law reform once achieved. Building alliances and working as a coalition allows many different actors to play a role, each bringing their own specialism and audience, and demonstrating support for law reform across different sectors. Children can be involved in all stages of campaigning, participating in achieving change on an issue of key concern to themselves.

Almost 1 in 3 boys and 1 in 8 girls, aged 13-17 years old (school age), in Indonesia experienced physical violence in the past 12 months[1]. This has shown no significant improvement since 2015. According to the Global School-Based Health Survey, 32 per cent of children aged 13–17 years had been physically attacked in the past 12 months, while 20 per cent had been bullied. This indicates that investment in safe school environments and anti-bullying programmes is necessary, and it will also improve the learning outcomes.

"My teacher used to pinch me when I didn’t do my homework. I always do my homework afterwards," an elementary student[2].

This quote represents the realities of corporal punishment that are still faced by children in Indonesia today, not only in rural but also in urban areas. Punishment of this nature is referred to in several ways, for example: hitting, pinching, smacking, spanking, and belting. Corporal punishment is violence inflicted on children by parents, teachers, carers and others, in the name of “discipline”, and is experienced by a large majority of children in many states worldwide[3].

A full understanding of the current legal status of corporal punishment in all settings is crucial in order to achieve effective corporal punishment prohibition. Indonesia has ratified several conventions related to corporal punishment, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child through Presidential Decree 36/1990, and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment through Act Number 5/1998. Through the ratification of these conventions, the Indonesian Government has showed their commitment to abolish corporal punishment. Moreover, in its third/fourth state party report to the Committee on the Rights of the Child, dated October 2010, the Government stated it had a programme to develop “national and regional regulations that prohibit all forms of physical and psychological punishments of children at home and in schools”.[4] Indonesia is also one of the Pathfinding countries at the Global Partnership to End Violence against Children.

Though Indonesia has ratified many global conventions, the country is still facing a challenge on the legal framework to end corporal punishment. During the Legal Reform Workshop on Corporal Punishment of Children in Yogyakarta, Indonesia on 8-10 April 2019, the Head of the Child Protection Department (Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection) reported there are 50 national regulations related to children’s rights and child protection that have not comprehensively defined corporal punishment yet. Protections against violence and abuse in the Penal Code, the Law on Child Protection, the Law on Human Rights, the Law on Domestic Violence and the Constitution are not interpreted as prohibiting all corporal punishment.

Corporal punishment has become “normalised” in societies and the task of changing a deeply rooted set of traditional, cultural or religious beliefs and practices, can sometimes feel impossible. This may lead to diverse resistances at all level. For example, mistaken assumptions that prohibiting corporal punishment will criminalise lots of parents, and children will be taken away from families. Social norms also play an important role leading to the legitimising of corporal punishment in order to make children obey teachers/parents/caregivers. In practice, there are still norms that contribute to continued acceptance and practice of corporal punishment; for example, awareness and understanding of child rights is low, and beliefs such as ‘adults know best so children should obey adults’. Religious and community leaders can play an important role in changing the mindset and behaviour of caregivers.

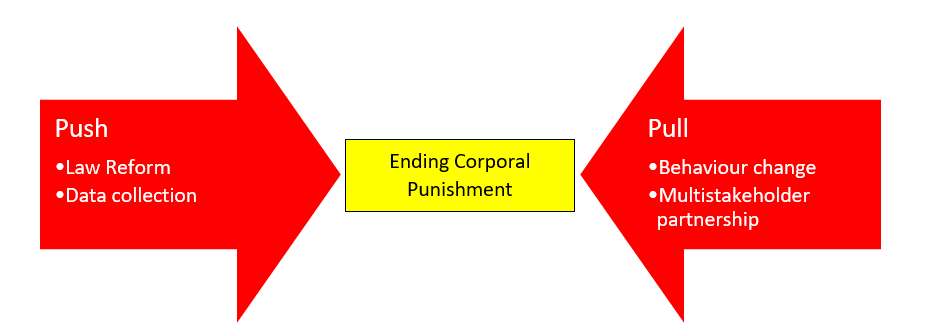

Two-ways approach: Push and Pull Strategy to End Corporal Punishment

The Push and Pull strategy is about working together to move public and policy makers through their journey to end corporal punishment. Save the Children Indonesia together with 20 other NGOs are collaborating under the CSO coalition on Ending Violence against Children. The coalition has developed a strategy on ending corporal punishment in Indonesia for the period 2019-2024. It covers the following:

The Push strategy is to bring the urgency of corporal punishment to the policy makers. While the pull strategy is about bringing knowledge and awareness of the benefits of prohibiting corporal punishment to the public. Therefore, the Indonesia strategy to End Corporal Punishment 2019-2024 consists of:

- Advocacy on law reform through dialogues with the parliament members and respective Ministries, initiation of child’s rights caucus in the parliament, and development of a roadmap towards ending corporal punishment.

- Develop integrated-data system on corporal punishment that aims not only to support the law reform processes but also for further evidence-based interventions. This will involve the academe and research organizations.

- Behaviour change towards corporal punishment by involving key influencers such as religious leaders, community leaders, parents, children, youths, teachers, and private sector. This will focus on bringing all non-state actors onto the same page, in understanding the impact and benefit of ending corporal punishment on child development, and considering how the public can start eliminating corporal punishment in their communities.

- Build partnerships on ending corporal punishment with all respective stakeholders to accelerate action to tackle the corporal punishment that children face. This partnership will not only relate to child-focused organisations but also to the human rights groups and private sector, highlighting Indonesia as a 'Pathfinding country' wishing to lead the movement to end all forms of violence against children.

Save the Children in Indonesia is currently implementing a project from 2018-2021 that works with government to create enabling policies for teachers and parents to improve literacy, and replace violent practices with positive discipline. Importantly, it enables children to understand their rights, and strengthens violence monitoring and reporting mechanism for quicker resolution. By reflecting the push-pull strategy, the approaches are:

- Advocacy on law reform: Code of Conduct to ensure a safe environment for children to learn in school will be in place.

- Develop integrated-data system: Child Protection reporting mechanism will be developed so that it will strengthen the effort of preventing and responding to violence against children in school-setting.

- Behaviour change towards corporal punishment: teachers and parents will be trained in positive discipline, including parenting without violence and awareness raising campaign at the community level.

- Build partnership on ending corporal punishment: building up the alliance on ending violence against children that will consist of multi-stakeholders at district level.

Indonesia has a high commitment to the implementation of Sustainable Development Goals, putting strategies and resources towards achieving the targets, including target 16.2 - to end abuse, exploitation, trafficking and all forms of violence and torture against children. Through the spirit of Leaving No One Behind, Indonesia is challenged to make the commitment into reality. So that all children will live free from violence by 2030.

[1] Gender Thematic Statistic: Ending Violence Against Women and Children, MoWECP, 2017.

[2] Project report, Save the Children Indonesia, 2019

[3] Globall Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, 2016, Corporal Punishment of Children: Summary of Research on its Impact and Associations, http://www.kodomosukoyaka.net/pdf/2016-GI-summary.pdf.

[4] 31 October 2012, CRC/C/IDN/3-4, para. 76

Legal Reform Workshop on Corporal Punishment of Children in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 8-10 April 2019

Guest writer

Ratna Yunita, Child Rights Governance Advisor, Save the Children Indonesia

Ratna has been a children's rights advocate in the development sector since 2004. With an educational background of Master in Public Policy, International Communication in the Netherlands, she has focused on development issues such as poverty, inequality, education, health, involvement of children and young people, and has been published several times. Ratna has been involved in the negotiation process of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agenda promoting the fulfillment of children's rights in Indonesia, the Asia Pacific region and globally. Her responsibilities include monitoring and demanding children’s rights throughout the United Nation mechanisms; the Indonesia Child Rights Situation Analysis (CRSA); conducting consultations to ensure the children’s views are recognized and taken into account by the policymakers through formal mechanism on children participation; and advising business sectors on the implementation of Children’s Rights and Business Principles (CRBP). In 2017, she took part in the UNESCAP validating guidelines for Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships for SDG implementation in the Asia Pacific region.

Contact: ratna.yunita@savethechildren.org

Related resources