Corporal punishment of children and public health: What does the research tell us?

Over the past five decades researchers have been gathering evidence about corporal punishment. 300+ studies involving hundreds of thousands of children have now been carried out, and the results are in: from being trivial, research shows that corporal punishment has significant negative impacts on the lives of children in the short and long term, with consequences and costs for society as a whole.

A webinar on 5 October, hosted jointly by End Violence and the World Health Organisation, aimed to promote understanding of the evidence surrounding corporal punishment of children, applying a public health lens and reflecting on strategies for ending corporal punishment.

In his introduction, Etienne Krug, Director of Social Determinants of Health at WHO highlighted how for so long corporal punishment has been considered normal and maybe even necessary, but now a growing body of research tells us that corporal punishment is a key public health issue, causing harm to children for the rest of their lives. In the light of this evidence we must take action to eliminate it, both because violent punishment is a violation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, but also because unless we do we won’t achieve SDG target 16.2 eliminating violence against children.

Professor Elizabeth Gershoff, of the University of Texas, described how corporal punishment is a public health issue because it is prevalent, it physically injures children, it impairs development, it is universally harmful, and costly to society. She explained how corporal punishment increases likelihood of drug use, moderate to heavy drinking and suicide attempts in later life, and has no association with any beneficial effects.

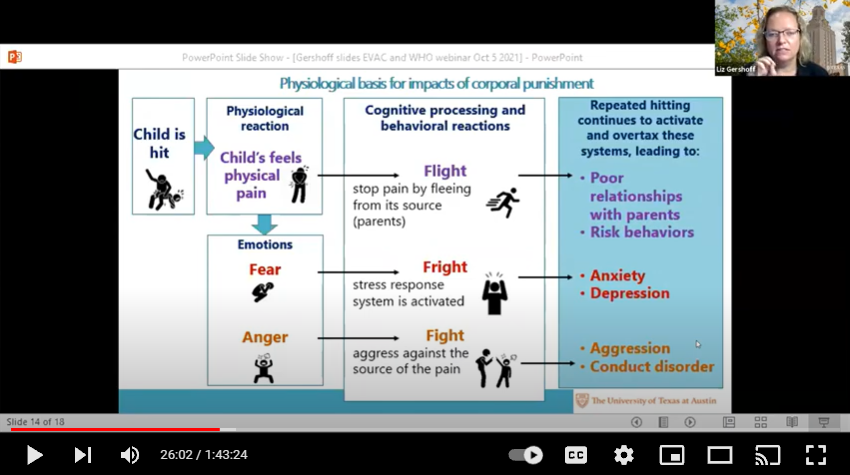

In her own research Professor Gershoff has found that children who are corporally punished have more mental health, cognitive and behavioural problems, and explained how the negative effects of corporal punishment, including the pain and physiological disturbance, remain consistent across cultures no matter how normative it is. She ended with the good news that corporal punishment is entirely preventable by implementing good public health measures.

Jorge Cuartas, from Harvard University, underlined how corporal punishment is widespread around the world – studies suggests that two in three of all children under five are subjected to violent punishment, with high prevalence seen across all regions. Rates have increased higher still during the Covid pandemic.

Cuartas explained how corporal punishment can undermine brain development with long-term impacts; exposed children exhibit high hormonal reactivity to stress, likely due to the physiological stress caused by the violent punishment. The impacts include reduced differentiation between fear and safety cues, increased reactivity to negative experiences, and overload of biological systems. Corporal punishment is linked to change in brain structure, including reduction in volume of prefrontal cortex in adults exposed to corporal punishment, and children who have been ‘spanked’ exhibited similar atypical neural activation to those subjected to severe physical or sexual abuse.

Given the increased risk of corporal punishment during Covid Jorge Cuartas finished by calling for the urgent implementation of support for parents, mass education campaigns and legislation prohibiting corporal punishment of children in all settings.

Professor Joan Durrant, from the University of Manitoba, discussed the measures needed to address the monumental and cascading costs of corporal punishment to society, highlighting how physical maltreatment (which is largely corporal punishment) costs $39.6billion USD a year in the East Asia Pacific Region alone.

Professor Durrant explored how the INSPIRE strategies can be used to eliminate violent punishment, in particular enactment of legislation and measures to change norms and values. She described the reduction in prevalence and changes in attitudes to corporal punishment observed in countries that have enacted and implemented prohibition, such as Sweden and Germany. Comparative research has addressed whether law reform or public education bring about change, pointing to the powerful combination of both providing a clear message in law as well as support for parents and other to move towards a new understanding about use of violence in discipline.

Dr Sonia Vohito, Legal Policy Specialist at End Violence highlighted the human rights imperative of prohibiting corporal punishment, as specified in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, and therefore an obligation of all ratifying State parties.

She described the five stages of putting a prohibiting law into practice, including a planned approach, with a communications campaign, support for parents, and monitoring and evaluation of the effectiveness of the ban. Dr Vohito also announced the publication of new research summaries available from the End Violence Partnership, detailing the evidence of impacts and associations of corporal punishment.

In closing remarks Dr Howard Taylor, Executive Director of the End Violence Partnership, highlighted the prevalence – but also the preventability – of corporal punishment. He celebrated progress so far, with 63 countries now implementing a ban, but urged that we must do more and go faster, with significant action essential in the next ten years. He called on all remaining countries to commit to prohibiting corporal punishment by 2030, and to accelerating the implementation of prohibition by making parenting support available to all and fostering the development of safe schools and communities.

Dr Taylor committed the End Violence Partnership to supporting countries on their journey tackling violent punishment, working together to ensure every child grows up safe and secure.